Back to the future: Lessons from half a century ago, for brighter prospects

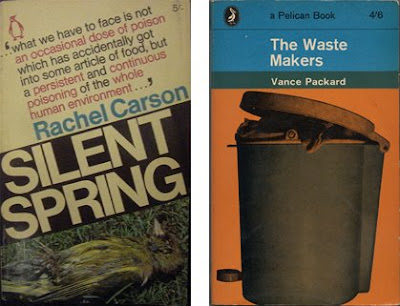

When I first came to London, I was quite amazed at what I saw in the capital’s parks. I was able to walk around with the company of squirrels and foxes, sharing the greens with them. Thinking of thousands of cats and dogs wandering around in cities in my native Turkey, this was quite a paradigm shift in terms of what a metropolis can accommodate as street animals. Reading Silent Spring further startled me, when I learned about how normal it was to have many other animals as part of urban life in the sixties. This book was written when this natural harmony all started to fall apart, it includes some of the first resistance attempts against cruel industrialization:

The ‘control of nature’ is a phrase conceived in arrogance, born of the Neanderthal age of biology and philosophy, when it was supposed that nature exists for the convenience of man. The concepts and practices of applied entomology for the most part date from that Stone Age of science. It is our alarming misfortune that so primitive a science has armed itself with the most modern and terrible weapons, and that in turning them against the insects it has also turned them against the earth.

If a visit to the electronics store today still gets you all mixed up, welcome to the club. Nowadays, it requires a good deal of effort to keep up with the pace of “development” in consumer goods. Nevertheless, one has to admit that no matter how amazed we might get at these new products, we have adapted so that we now accept that, for instance, an appliance we buy today will be out-dated in 6-12 months. But The Waste Makers was written at a time when concepts like “the consumerist society” and “planned obsolescence” were just introduced and still subject to debate. Therefore, like Carson, Packard finds things, which we are nowadays dull about, very difficult to understand:

How can the modern consumer choose plywood furniture intelligently—in the absence of a wood-labelling law—when wood labelled ‘driftwood walnut’ or ‘silver oak’ contains neither walnut not oak?

These two books belong to a time when people did not settle with the life the “common” understanding of economic growth and development had to offer them. It is a pity that nowadays that understanding is more or less the same, but the majority of people are okay to settle with it.

One question comes up after reminiscence: Did it, and does it still, have to be this way?

Labels: books, consumerism, ecology, planned obsolescence, WWII

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home